The adventurous palate of foodies and their #willtravelforfood motto are interesting phenomena.

The trend mentioned in a recent lecture intrigued me and moved a university student in the audience to ask Dr. Kristine Michelle L. Santos if Filipinos of yesteryear inherited their fondness for food from the Americans during the colonial era.

Santos, an assistant professor at Ateneo de Manila’s history department and Japanese Studies program, was taking questions after her lecture last Sept. 30 at The Rockwell Club. She was the final speaker of the six-part “Cultural Intersections: The American Period” lecture series presented by the Lopez Museum and Library. She discussed how feasibility and motivation shaped food tourism in the Philippines in her lecture titled “Food Trips: Food Tourism during the American Period.”

“Accessibility to food is key here because it makes it easier to indulge in it [today]. The parties then had [an abundance] of food, but they weren’t frequently available and done. Lifestyle [also made] the difference because, in the past, automobiles weren’t available,” Santos said.

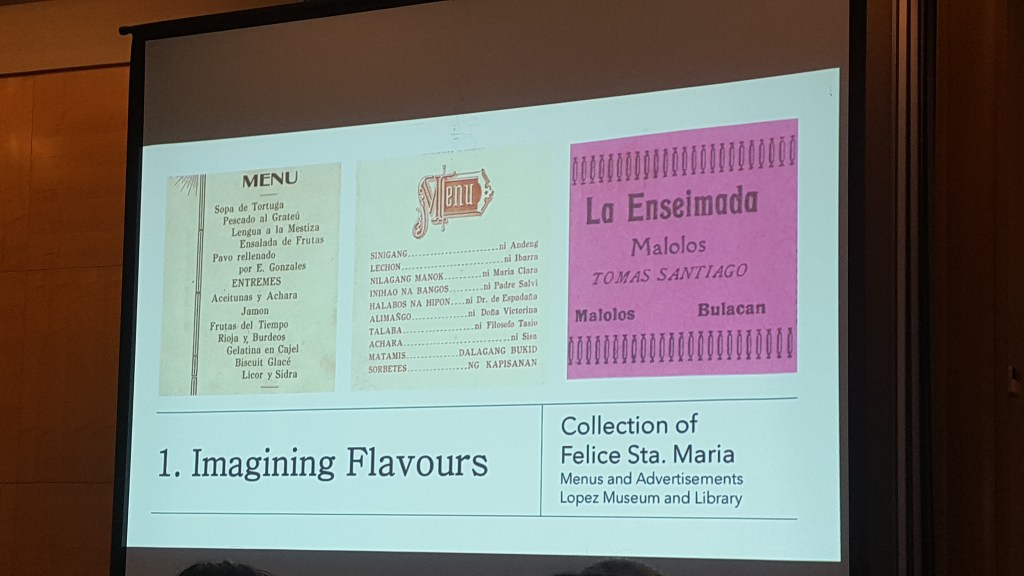

To illustrate the difference in milieu, she pulled up onscreen two menus and an ad of La Enseimada of Malolos, Bulacan, from the collection of culinary historian Felice Sta. Maria. Menu No. 1 offered the popular specialty of that era, sopa de tortuga, or turtle soup. Menu No. 2 had dishes inspired by Jose Rizal’s novels—Ibarra’s roasted pig, Maria Clara’s boiled chicken, Padre Salvi’s grilled milkfish, and Sisa’s pickled papaya.

Pointing at the menus, Santos asked her audience: “Would people travel all the way to Bulacan to eat?”

Would the gourmands have done so?

“The reality was they wouldn’t travel for food because it hardly figured in their imagination during the American occupation,” she said.

Where’s my ride?

Making a trip to Bulacan to enjoy turtle soup hinged greatly on having a vehicle to get there. This became achievable with “Plymouth [and other] imported cars from the US” entering the Philippines during the American colonial era.

“It made travel feasible because people now had personal cars,” Santos said in her lecture.

The entry of Philippine Airlines into the transportation scene also made travel much easier compared to when there were only “animal-driven vehicles, boats and ships, and the Philippine National Railroad,” she added.

Boats were the main mode of transportation in the country in pre-Hispanic times. In her book “Pigafetta’s Philippine Picnic—Culinary Encounters during the first circumnavigation, 1519-1522,” Felice Sta. Maria wrote that Ferdinand Magellan met nine men from Zuluan, Samar, who came in a boat, after he landed in the Visayas and set up camp at Homonhon.

Magellan and crew exchanged goods with the natives, the latter matching the Spanish explorer’s red caps, mirrors, combs, bells, ivory, etc., with fish, two coconuts, a jar of arrack, and bananas. The natives returned in two boats to give Magellan the “coconuts, sweet oranges, and a jar of palm wine” he had bought.

Sta. Maria wrote that the boats were either a small baloto (or baroto) used by the common folk like the nine men, or the huge 15- to 25-meter balanghai (or balangay or barangay) that carried the natives’ king and his gifts of “a bar of gold and a basketful of ginger” for Magellan.

“Food was the first Filipino gift to the Europeans in Philippine territory … Food and wine functioned as a language of possible friendship or tolerance. Strangers to each other, the locals and [Magellan] met on … Homonhon Island,” wrote Sta. Maria.

According to Santos, the ease that automobiles and airplanes afforded travelers affected motivations as well, so that choices were now based on work, social networks, and leisure time. Tellingly, the traveler was often a male foreigner assigned in Manila, or “afam,” she said, drawing laughter.

Travel stories

Santos grouped the afam into three categories, the first composed of American civil servants, explorers, journalists, and photographers. Their travelogues focused “on how the land looked like and the resources available in the country.”

Food was a mere coincidence, like in Eugene Ressencourt’s report “Vagabonding through Mindanao” published in Philippine Magazine (1932). Santos noted that the self-described “gentleman vagabond” wrote about the “abundance of tropical fruits in his very yard,” but was vague about the good breakfast he had one Monday morning.

It was different with the second afam category composed of entrepreneurs and their wives, including the likes of Mrs. Campbell Dauncey, “a woman educated in domestic sciences, … focused on how to run her home [and] resources.”

Santos highlighted how the Iloilo-based Mrs. Dauncey detailed coffee brewing in “An Englishwoman in the Philippines” (1906): “[The] excellent black coffee made in the native fashion by holding the ground in a little bag at the end of a piece of bamboo in a coffee pot—simple, but effective. With it went large flat cakes of yellowish sugar called caramelo, and she had also produced from somewhere four ship’s biscuits …”

Gender dictated the mention of food in articles because, Santos explained, “food was domestic, [and thus] gendered. It wasn’t in the culture of men then to pay attention to flavors. They discussed other topics. They’d eat and leave.”

Educators formed the third afam group whose food experiences were connected to meals at the Teacher’s Camp in Baguio, where the menu finally included nilaga, a considerable feat in the trend of Western menus indicating that a fight for recognition of Filipino cuisine was well underway.

Significantly, as travelogues abounded, adverts promoting dining options started appearing everywhere, pointing to the country’s growing food-and-travel landscape.

“It was possible to travel. There were places to eat [and] a recognition for a need to have a place to gather,” Santos said.

Restaurants became the venues for get-togethers and go-to places for, say, ice cream and candy, like Clarke’s on Escolta, Manila. In Zamboanga, Mrs. Smith café was the chosen spot. Hotels like The Manila Hotel and Orient Hotel became important and posh places for gatherings. Their menus implied a sea change in the diners’ palates. Orient Hotel’s 1901 New Year party menu showcased Australian turkey, lamb, and mutton, which, Santos observed, signaled a notable shift from the traditional preference for Spanish cuisine to American.

Frozen foods

Advanced food technology—modern transportation’s twin—strengthened the country’s food tourism. Comparatively, fermentation was customary among Filipinos in pre-Hispanic times. This culinary process didn’t escape Pigafetta’s observation, especially the use of coconut—i.e., coconut vinegar—in Philippine cooking, wrote Sta. Maria. Up until then, Pigafetta apparently only knew grapes as the main ingredient in vinegar-making, as was the practice in Spain.

But preserving food for long-distance travel was a perennial problem even ‘two centuries after Magellan’s voyage,’ wrote Sta. Maria.

Quoting Gemelli Careri (1651-1725), an Italian leisure traveler onboard a Spanish ship in the 17th century, she wrote: “Fresh vegetables and fruits had to be eaten immediately after boarding the ship. The lack of vegetables and fruits [in] long journeys caused fatal illnesses [like] scurvy and beriberi. Vizcocho [sea biscuit] bred weevils that overran the boat and everything, and even attached to the human body.”

Santos said the advent of cold storage and refrigeration revolutionized food production and distribution in 20th-century Philippines. Cold storage led to ice plants and a rise in the popularity of ice drop, the 1930s Depression-proof snack. Refrigeration enabled restaurants to regularly offer cold drinks and ice cream, both becoming staple menu items to this day.

Combining cold storage and modern transportation made Mrs. Dauncey’s life in Iloilo with “London-priced bananas [and] miserable tomatoes and eggplants” more bearable, Santos said.

Referring to Mrs. Dauncey, Santos said that “once a week [she] got provisions from the Cold Storage in Manila—Australian meat and butter, and sometimes vegetables, but this is only a private enterprise of a few of the English community, who club together and get an ice-chest by the Butuan, the weekly Metro mail.”

Home economics

The American way of life permeated the agricultural sector, creating opportunities for communities to integrate food into their livelihood. School children in Guinobatan, Albay, for example, learned farming where “the boys tilled the land and women figured out what to do with the harvest,” Santos said.

Introducing domestic science, aka home economics, in the Philippines, Santos said, was a positive development vis-à-vis having new colonizers working towards a goal of healthier Filipinos. The Americans observed that Filipinos were suffering from malnutrition, one of the Philippines’ key problems that they identified.

Teaching cooking had a concomitant improvement on travel, which became necessary in demonstrating the American recipes to the community, in “teaching people how to prepare and serve food,” Santos said. It also ushered in a new occupation for women who, as “demonstrator,” toured and taught at “demonstrations,” or teaching forums. One popular demonstration was on corn and making corn cakes, corn bread, etc., in Cavite in 1912, when hope for agricultural success was pinned on growing corn.

Although domestic science bound women to the kitchen, it was catalytic in shaping what Santos labeled as Filipino food culture.

Food fight

Fusing with heightened nationalism and feminism, a strong resistance to American cuisine and imported ingredients developed, per Santos. Women like Manila Carnival Queen Pura Villanueva Kalaw and Filipino educators championed the recognition of Filipino cuisine and local ingredients. In fact, Kalaw’s cookbooks fought for Filipino food identity: The recipes featured, the origins of which she identified, weren’t always from Manila.

The advocacy for Filipino food extended to lobbying against the massive importation of American products. Bolstering the fight was the government’s policy of protectionism amplified by the National Economic Protectionism Association, established in 1934, which prioritized Filipino businesses.

“[Using] Filipino ingredients gave food a local identity and discovering the ingredients that fit our palate,” Santos said. “Local food tourism was [also] spurred through the industries—i.e., fish or Iloilo coffee—and demand.”

Santos went on to clarify that Filipino ingredients were never actively banned by the colonizers, who just never thought of using them until much later. However, bagoong was omitted—or perhaps banned?—from the recipes despite fermentation being taught in schools.

The innovations continued, expanding to menus with Filipino dishes. Thus, Filipino mangoes were turned into candy and papaya into sauce as local food innovations bucked the trend of using imported ingredients.

Local palate

Gourmands were now willing to go the distance for food, mostly to parties offering thematic menus. One menu in Tagalog that Santos projected onscreen was for a party in 1932 for teachers and officials of the local government unit of Hagonoy, Bulacan. Partygoers were to feast on dishes reflecting moral values: stated in Tagalog, salad of truth, fish in a soup of cooperation, chicken of proper work, shrimp of glowing fellowship.

A separate menu for a Toastmaster event followed a similar concept, but featured English-named dishes—i.e., attentive pickles, peaceful olives, enchanting fish, progressive michado (sic) and potatoes, and charming rellenado and school endive.

Santos added that other menus made some communities, like the Chinese, visible, but Chinese dishes were still a rarity.

Local specialties like La Enseimada from Malolos, Bulacan, thrived (and continues to do so to this day). A recent video of broadcaster Korina Sanchez’s interview with the bakers, which Santos played for the audience, reveals that the original recipe remains untouched, making the pastry laden with butter, cheese, and salted egg a top pasalubong among tourists.

Filipino food went head-to-head against the hegemonic American cuisine in asserting its identity. It was victorious, and dishes like puto, calamay, and adobo moved to the main dining table from the dirty kitchen.

But the journey of Philippine food tourism continues, opening new academic inquiries and research.

Vegetarianism

During the Q&A portion, a lecturegoer asked if Filipinos were inclined to vegetarianism. Another member of the audience replied that it was possible considering that the recipe books of Maria Orosa and Kalaw highlighted vegetable dishes.

Santos pointed out: ‘We had a strong vegetarian cuisine back then, but something changed.’

Another lecturegoer followed up on Santos’ opinion and attributed the dietary changes to the introduction of the meat-heavy American diet into the country.

Meanwhile, my mind swirled with questions on social class and food tourism. Was there complete acceptance of Filipino food among the colonizers, or was it an act of benevolent tolerance? Were local ingredients seen as déclassé? Did Filipino food widen the gap between the wealthy and poor Filipinos? Case in point: The proponents of Filipino food came from the elite class.

Food is good, magical even, but it isn’t available to everyone. Didn’t our history teach us against complacency toward people bearing gifts? They aren’t always moved by magnanimous motivations.

Leave a Reply